Walkable Land in the North Sea

Walkable Land in the North Sea

There is an area of shallow sea that links Holland with East Anglia. It is likely that this passage would have provided walkable land between England and Holland until a time when Neolithic people were exploring Northern Europe.

The bathymetry chart above indicates this broad area of shallow water joining Lincolnshire, and Norfolk, in England to Holland. Elsewhere, to the south of this region deep water gullies would have prevented any migration by animals, people, or plants.

The Norfolk Banks (above) are a series of ridges on the floor of the North Sea, beside the Norfolk coast.

Detailed chart, above shows bathymetry of ridges and troughs of the Norfolk

The location of this section of the Norfolk Banks, above, is indicated on the plan above it.

The main features of the Norfolk Banks that can be seen in the plan and section are as follows

1- the high ridges of these banks are parallel to each other.

2- the ridges rest on a flat surface which is about 35 metres below sea level here.

3- the ridges are also parallel to Bathymetric lows, gullies that are also linear, and run immediately beside the ridges. These gullies are cut into the flat surface upon which the ridges rest.

4- the gullies lead off in a southwestern direction, attaching to , and becoming part of the Lobourg Channel, a deep water channel in the middle of the Dover Strait.

5- the Norfolk Banks have not moved in the last 100 years, and are unlikely to have ever moved.

6-at nearly 2 kilometres wide these features are massive.

My assumption is that the peaks of these ridges were once part of a land surface that joined Holland to East Anglia. Subsequent sea level rise here has partially removed seabed sediments, leaving these ridge Formations, the Norfolk Banks.

The Lobourg Channel which merges with the Norfolk Banks is a deep gully in the floor of the Dover Strait. It connects with the Norfolk Banks at the North and with similar features in the floor of the English Channel between Dover and Southampton.

The gullies between the banks of the Norfolk Banks are continuous with the gullies in the Dover Strait, (the Lobourg Channel, below) and also with gullies in the English Channel which have been dated to 21,200BP.

This date , 21,200BP, is generally accepted to be close to the coldest point in the last ice age, and the start of the process of deglaciation of ice sheets over the northern hemisphere, and the group of gullies represents the southern limit of the ice sheet over Britain that melted at that date.

The chart of the southern North Sea, above, indicates a plausible sketch of contours for the likely depth of ice as it lay on Kent, East Anglia, the Dover Strait, and southern North Sea before 21,200BP.

The contours are for 100, 50, and for 5 metres of ice depth.

The actual weight of ice on the 100 metre contour line would have been 90 tons per square metre. The weight of ice on the 50 metre contour would have been 45 tonnes per square metre, and the 5 metre contour, 4.5 tonnes per square metre.

The effect of the thick ice on the Dover Strait would have been to compress pre-existing sediments there. This compression of sediments squeezed out all the air and water held in them, causing a condition which geologists describe as "overconsolidated". From personal experience I can say that this overconsolidated material is as hard as hell!.

This means that sediments against the Norfolk coast would have been a rock hard material, while the sediment under the areas closest to the Dutch coastline would have remained relatively a great deal softer.

After 21,000BP the surface of Britain thawed, and the ice sheet retreated. By about 15,000BP the ice sheets were mainly restricted to the Highlands of England and Scotland, and the walkable land between Norfolk and Holland permitted the migration of herbs and trees, and animals to move north across the whole of the country.

At 7000BC the British Isles were forested, and in Orkney "A charred hazel nutshell from the mound at Long Howe produced a radiocarbon date (SUERC-15587 7900±35 BP 7030–6640 cal bc 95% confidence)." Also in Orkney there were Willow, Birch, Heather, hawthorn, Pignut. Plum/Cherry charcoal scraps present in the hearths of people living in the late 4th millennium BC.

Herbivores, followed the plant life, while carnivores followed the herbivores.

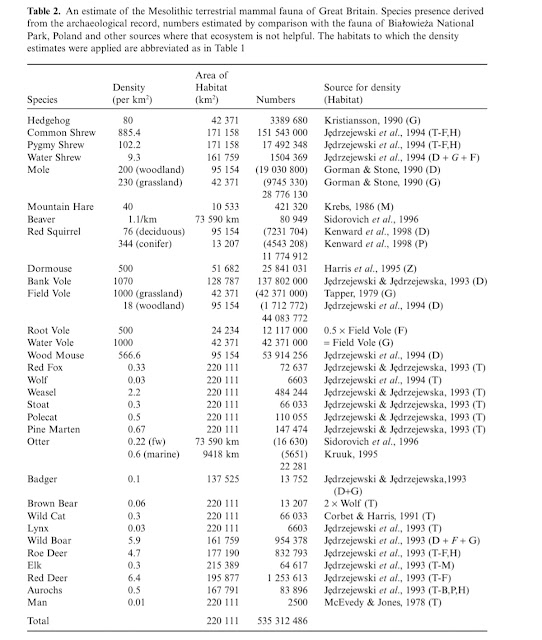

Those animals that are known to have made this journey and to have visited Britain in around 5000BC, are recorded in "The Mesolithic mammal fauna of Great Britain", by Maroo and Yalden.

....and in Orkney Animal bones radiocarbon dated to the Neolithic period include:-- sheep, wild pig, auroch, Red Deer, possible wolf, dog, pine marten, wood mouse, and Orkney Vole.

In "New evidence on the earliest domesticated animals and possible small‑scale husbandry in Atlantic NW Europe" by Philippe Crombé et al, the authors provide evidence that people in Neolithic Europe were developing forms of agriculture, including herding or shepherding of domesticated animals into the late 5th millennium.

The growth of herder communities in Northern Europe, described above neatly merges, in timescale, with the plan of Neolithic movement in Britain in the 4th millennium BC, as outlined by Alasdair Whittle , in "Whittle, A., Bayliss, A. & Healy, F. 2011. Gathering Time:Dating the early Neolithic enclosures of southern Britainand Ireland." See image below...

Crombe dates the presence of people in the Swifterbant as follows:- "It was the start of a totally new lifeway which probably would culminate into a fully agrarian society in the course of the second half of the 5th millennium cal BC, around 4000 cal BC at the latest."

He also suggests that the Neolithic people who crossed from northern Europe to south east England were animal herders, and the presence of both sheep and dogs in Neolithic Orkney rather confirms that theory. In his discussion he also offers that there was a transition away from hunter-gatherer behaviour occurring, but this is not borne out by the evidence from the middens of the Knap of Howar in Orkney where it is clear from animal bones, bird bones, and molluscs found in them that the people who lived there would eat anything that came to hand.

At a date during the 4th millennium BC sea-level rose sufficiently that it would erode soft sedimentary deposits against the Dutch coast of the North Sea. Hard deposits that had been overconsolidated by the ice sheet over England were not eroded, but remained as the ridges of the Norfolk Banks.

The woodland that had grown on this land between Norfolk and Holland was then washed away as the waters of the Atlantic Ocean pushed through to the newly developing North Sea.

As the English Channel was scoured out ,only the compacted ridges of the Norfolk Banks remained in the floor of the southern North Sea.

*

If i have successfully suggested that Neolithic people walked from Holland to Norfolk without getting their feet wet, it makes sense to reconsider whether the same could not be true for land between Caithness and Orkney.

See:-"Swifterbant Culture"

Next blog:- "Archaeology in the North Sea"

Sources

"The geology of the southern North Sea. United Kingdom offshore regional report" By T D J Cameron, A Crosby, P S Balson, D H Jeffery, G K Lott, J Bulat and D J Harrison

New evidence on the earliest domesticated animals and possible small‑scale husbandry in Atlantic NW Europe" by Philippe Crombé et al

*

All views and opinions expressed are my own.

Jeffery Nicholls

Orkney

Jiffynorm@yahoo.co.uk

Addendum

If you are interested, here is more evidence of where people came from, and when. The

Isotopic Evidence for Human Movement into Central England during the Early Neolithic by SAMANTHA NEIL CHRIS SCARRE, JANE EVANS , JANET MONTGOMERY.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of the individuals buried in the Whitwell cairn have strontium isotope ratios higher than 0.7170. High values are rare in human enamel in burials found inBritain (Evans et al., 2012), and all current evidence suggests that such values do not originate from the biosphere of central England (Evans et al., 2018).

Based on present understanding of the methodology employed and the way in which strontium isotope ratios within human enamel are derived, the results suggest that these individuals obtained the majority of their dietary resources from a geographical area in which high 87Sr/86Sr values are routinely bioavailable: for example, on granite or ancient basement gneisses.

British bioavailable values higher than 0.7170 have been recorded in plants growing in Scotland and on granites in Dartmoor in south-west England. In these regions, however, the appearance of Neolithic features does not significantly pre-date the Whitwell burials: current modelling of radiocarbon dates suggests that Neolithic material culture and practices only began to appear in southwestern England and Scotland in the decades around 3800 cal BC (Bayliss et al.,2011: 736, 822–24, 835–40). Strontium isotope ratios higher than 0.7170, comparable to those exhibited by the group at Whitwell, have been recorded in the biosphere on the Armorican Massif in northwestern France (Négrel & Pauwels, 2004;Willmes et al., 2013, 2018).

Recent analysis of Early Neolithic material culture found within Britain has been used to argue that there may have been population mobility between this area and Britain from approximately 3800 cal BC (Pioffet,2015; see also Sheridan, 2010a, 2010b).

Strontium isotope analysis cannot, on its own, determine the geographical source of the 87Sr/86Sr values found within human enamel at Whitwell: competing arguments for links to different source areas must, therefore, be evaluated on the basis of present archaeological and radiocarbon dating evidence. Based on current understanding of British biosphere 87Sr/86Sr data, the results do, however, provide evidence for individual human mobility over long distances during the thirty-eighth century BC, a period associated with the rapid spread of new cultural practices across Britain (Bayliss et al., 2011: 801).

Comments

Post a Comment